Pioneering Architects: Calvin T.S. Brent and John E. Brent

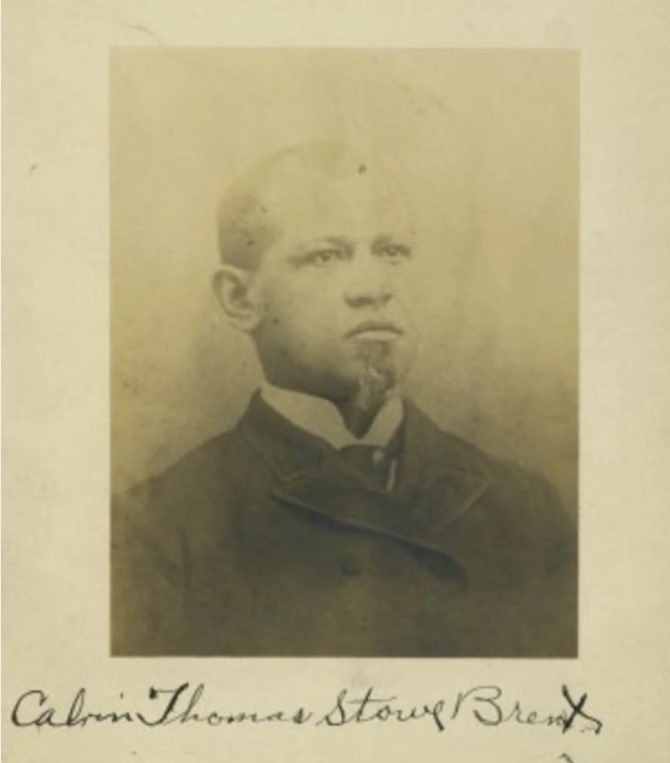

CALVIN THOMAS STOWE BRENT DESIGNED ST. LUKE’S EPISCOPAL CHURCH, BEGINNING WORK IN 1876

Fewer than one in five new architects identify as racial or ethnic minorities, and just about two in five are women, according to the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards. As we work to achieve a future of greater equity, diversity, and inclusion in the profession, we can learn important lessons in reckoning with the past. The Pioneering Architects series celebrates the legacy of architects who overcame unimaginable obstacles. In sharing their stories, we aim to pay overdue tribute to their talents, honor their courage, and learn from their experiences.

When Native Washingtonian Calvin Thomas Stowe Brent opened his office near 7th and E Streets in 1875 he made history. The son of a former slave, Brent is widely considered to be the first African-American architect to practice in Washington, D.C. Brent’s father, the first pastor of the John Wesley African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, purchased his freedom decades before and was a socially connected pillar of the African-American community, according to the historian and preservation activist Nancy Schwartz, writing in Dreck Spurlock Wilson’s seminal African-American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary.

CALVIN THOMAS STOWE BRENT

Brent’s apprenticeship period from 1873 to 1875 at a local firm headed by Philadelphia-born Thomas Plowman, an established white architect, is a noteworthy anomaly during the Reconstruction Era. This relationship proved to be fortuitous for Brent in another way: Plowman was the Inspector of Buildings for the District of Columbia. Brent’s training, scrupulous and demanding, would have been a cornerstone for his future success and arguably provided an advantage not emphasized at one of three existing architecture schools, barely in their infancy. In addition to the design, geometry, drafting, and structures skills he would have mastered at MIT, Cornell, or the University of Illinois, the on-site building safety emphasis he gained through his apprenticeship served him well. With modern-day regulations and labor laws still decades in the future, building safety in the District in Brent’s era was unevenly considered, at best, and his mastery of it would have been important to earning commissions.

Even with these specialized skills, a Black architect’s success in a segregated society was an uphill climb. Brent’s location may have proved critical. According to Wilson: “Two things made D.C. unique. One was Black society. Washington at that time had probably the biggest and wealthiest Black society in the United States. Second was the presence of Howard University. Those two factors essentially created a market for Brent.”

The son of a preacher, Brent would seem to have special access to another opportunity in the D.C. building market: projects for African-American churches. But it didn’t always work that way. “During that time period, the African-American ministers of the largest churches were leaders of the community and more or less were the conduit to the segregated white community of Washington,” said Wilson. “They wanted to make sure their communication to the white community – white business and government leaders – remained in a friendly posture. So whenever these ministers had an opportunity, especially a business opportunity, to involve whites, they would turn to the white community.”

It was yet another hurdle Brent overcame to earn his first commission: St. Luke’s Episcopal Church at the corner of 15th and Church streets. Work began in 1876 when Brent was 22 years old, and over the next 25 years, he would complete five more churches, two commercial buildings, and at least 82 houses. Today, 29 of his residential projects and two churches remain (including St. Luke’s, which was landmarked in 1976). The 100 or so building permits in Brent’s name as both architect and builder between 1876 and his death in 1899, were for projects in all four quadrants of the city, according to the District’s Office of Planning. For a city historically divided by race and economic opportunity, his body of work forms a map that transcends the geography of disenfranchisement in the nation’s capital. Brent’s work also fluidly addressed various 19th century Victorian expressions, mostly Gothic and Queen Anne, but with the occasional Italianate detail.

Calvin Brent’s name does not appear in the usual architecture sources, including the dozen or so guides about architecture in Washington, D.C., the American Architects Directory (published between 1956 and 1970), or 1984’s four-volume Macmillan Encyclopedia of Architects, once touted as “the most comprehensive assemblage of architectural biography ever attempted.” While inclusion does not necessarily confer legitimacy, Brent’s absence should challenge our credulity about so-called authoritative secondary sources.

The official record is similarly sparse when it comes to Brent’s son, John Edmonston Brent. But, like his father, the younger Brent left a lasting architectural legacy and community impact. Born in Washington, D.C., in 1889, John Edmonston Brent would go on to become the first African-American architect to practice in Buffalo, New York, active between 1921 and his death in 1962. In his first decade of work as an architect, Brent was part of a cohort of licensed Black architects in America that numbered fewer than 100 and landscape architects that numbered six. Two of Brent fils’ works have captured the attention of his biographers—both early signposts for the historic preservation movement: the YMCA on Michigan Avenue (1928), a handsome brick building and center of Black life in Buffalo that was demolished in 1977, and two cast iron gates for the Buffalo Zoological Gardens, which were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2013.

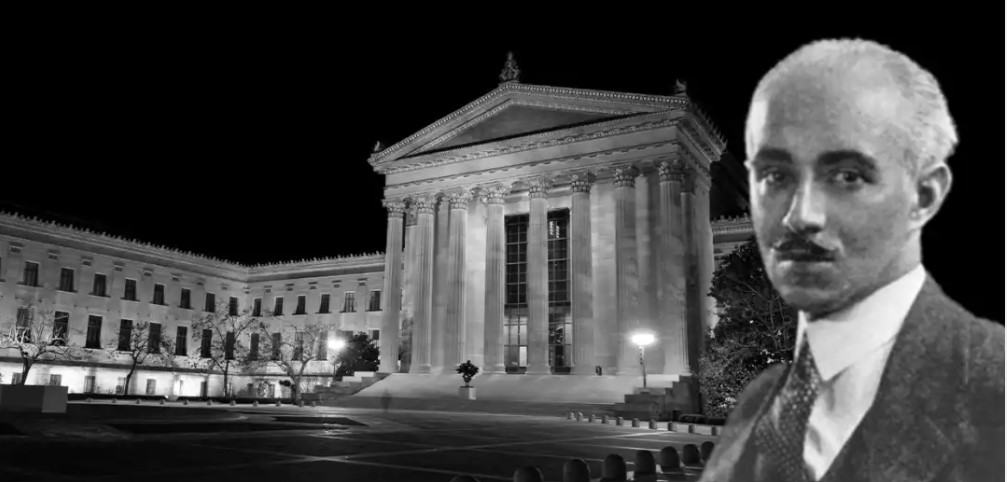

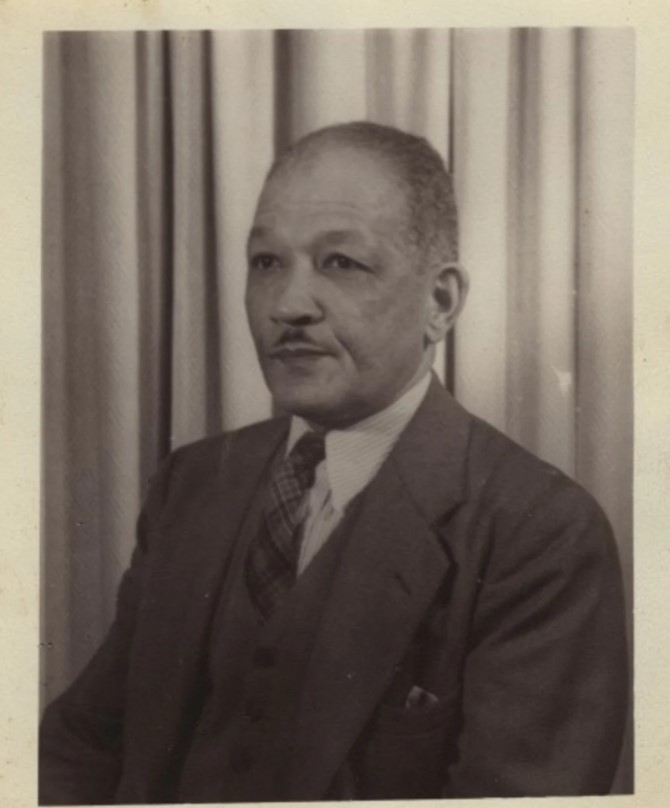

JOHN EDMONSTON BRENT

Brent arrived in Buffalo in 1912 after graduating from the Tuskegee Institute and the Drexel Institute of Art, Science and Technology in Philadelphia. Following an apprenticeship with Max Beirel, scion of two notable, old Buffalo families, Brent started his career, founded the Buffalo Branch of the NAACP, and joined the American Institute of Architects. Brent worked for several local firms over the next decade and a half, finally opening his own in between 1926 and 1935 at 99 Lonsdale Avenue in Hamlin Park, which would become a stronghold of the Black middle- and upper-middle class over the next 25 years.

The site of his most notable building, the YMCA at 585 Michigan Avenue just east of downtown, has been vacant since the wrecking ball took away its brick bonding, string courses, lintels, and interior walls 44 years ago. But for most of the 50 years before that, this Y served Buffalo’s burgeoning Black community with four levels of classrooms, dormitories, lounges, a natatorium, and a barber shop. YMCAs across the country were vital links in a network of places African-American men (and women, at the YWCA) could congregate and stay at a time when segregation severely limited their travel options. Sears & Roebuck CEO and philanthropist Julius Rosenwald financed 25 percent of the cost of 21 YMCAs in several states specifically to accommodate Black men with amenities that rivaled the Ys of white Americans.

An exhibit last year at the Buffalo Public Library detailed the project’s significance in Brent’s early career, as well as his work in greater upstate New York. As a center for Black life in Buffalo, it was a magnet for the increasingly mobile Black community in post-war America. W.E.B. Du Bois, Count Basie, and the Cleveland Browns’ Jim Brown (while he was at Syracuse) all visited. A few years after it opened, Howard University Art Gallery included Brent’s renderings and plans for the building in “Exhibition of the work of Negro-Architects.” Unthinkable as it seems that a center for African-American life in a city like Buffalo could be torn down, for many northern industrial centers of the Rust Belt, economics and demographics sounded the death knell for a lot of architecture in the post-war era, including Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Administration Building (1903-1950) and Richard Waite’s Grosvenor Library and Cyclorama (1871-1974).

Adjacent to Hamlin Park, less than two miles away from his first office, Brent’s most enduring work centered on the entry court and two iron gates for the 1875 Olmsted-designed Buffalo Zoo. But they represent more than beloved and familiar designs that generations of Buffalonians remember. They signify Brent’s longstanding work for the city’s parks department from 1935 to 1957, where he planned and designed 18 facilities and exhibits. According to New York State Historic Preservation Office (NYSHPO) historians Everett L. Fly and Ellen P. Hunt, writing in the National Register Nomination for Brent’s gates and forecourt, “Brent played a major role in transforming the layout of the zoo from an outline into an elaborately detailed neoclassical garden influenced by the City Beautiful movement.” Many of his contributions to the zoo have been lost over time during later renovations, yet the surviving Onondaga limestone veneer, Medina sandstone, wrought iron, and so-called “tapestry glass” of the gate lights manufactured by the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company that give the gates their distinctive heft and grandeur remind us that craft and integrity matters.

Although Calvin Thomas Stowe Brent and his son John Edmonston Brent might not have received their due in architectural records, their architectural legacy is a testament to obstacles overcome and barriers defeated.