Building a “Forever” Home

Building a “Forever” Home

We have all heard clients say, “This will be my forever home.” How can architects make that a reality?

Yet, HUD’s 2011 American Housing Survey showed that less than 5% of dwelling units have features needed by an ambulatory person with a disability, and less than 1% would allow a wheelchair user to live independently.

If there are two people living out their lives in a house, there is a 75% that one or the other will need some sort of accommodation. Clearly a ‘forever’ home must be able to adapt to changing needs.

If there are two people living out their lives in a house, there is a 75% that one or the other will need some sort of accommodation. Clearly a ‘forever’ home must be able to adapt to changing needs.

The main reason for the lack of accessible housing is that the ADA and and building codes don’t require it for single family homes. A handful of US cities have Visitability or Universal Design ordinances that go beyond their state’s building codes, but everywhere else, architects are mostly just responding to whether their clients ask for a more accessible design. For many details of accessible design, you could start by applying the accessible dwelling unit standards in Chapter 11B of the California Building Code (CBC), which we use for public multi-family buildings. But just as a bunch of good doors and windows don’t make a good house, a bunch of standard accessibility details don’t make good Universal Design.

For many details of accessible design, you could start by applying the accessible dwelling unit standards in Chapter 11B of the California Building Code (CBC), which we use for public multi-family buildings. But just as a bunch of good doors and windows don’t make a good house, a bunch of standard accessibility details don’t make good Universal Design.

Here are some design concepts you can incorporate without creating a home that looks specialized or institutional in any way. In many cases, successful accessible design simply means not creating unnecessary barriers to everyday tasks.

ENTRY: Start your design with the front door. Choose a spot where it’s easy to minimize the vertical differential between the arrival point (sidewalk, garage, or driveway) and the entrance. If you don’t start with this basic approach, it’s too easy to wind up with one or two steps at the entry that you can’t get rid of once the rest of the design is in place: a deal-killer for inclusive design.

ENTRY: Start your design with the front door. Choose a spot where it’s easy to minimize the vertical differential between the arrival point (sidewalk, garage, or driveway) and the entrance. If you don’t start with this basic approach, it’s too easy to wind up with one or two steps at the entry that you can’t get rid of once the rest of the design is in place: a deal-killer for inclusive design.

Even on a steep site this minimizes the number of steps, so a wider range of ambulatory people can use the stairs for more years. If there is an unavoidable step or two in the entrance sequence, include a beautiful handrail now. This isn’t just about living with disability, it’s about preventing one!

DECKS: Make patios and decks level with the interior floor. Picture a homeowner using a wheelchair, and on their lap is a plate with a nice ribeye steak fresh off the BBQ. Even a one-inch threshold is a real impediment, not to mention a full step. As a wheelchair-riding barbecuer, I know this to be Truth. And as an architect, I know that a truly level transition creates a dramatically stronger connection to the outdoors and better flow for everyone.

DOORS: Use 36 inch doors everywhere. Chapter 11B requires a minimum 32 inches clear width at doors, but extra space means crutches or a wheelchair user’s elbows fit more comfortably, and door jambs avoid getting scratched up. And it’s especially helpful when someone needs to move furniture.

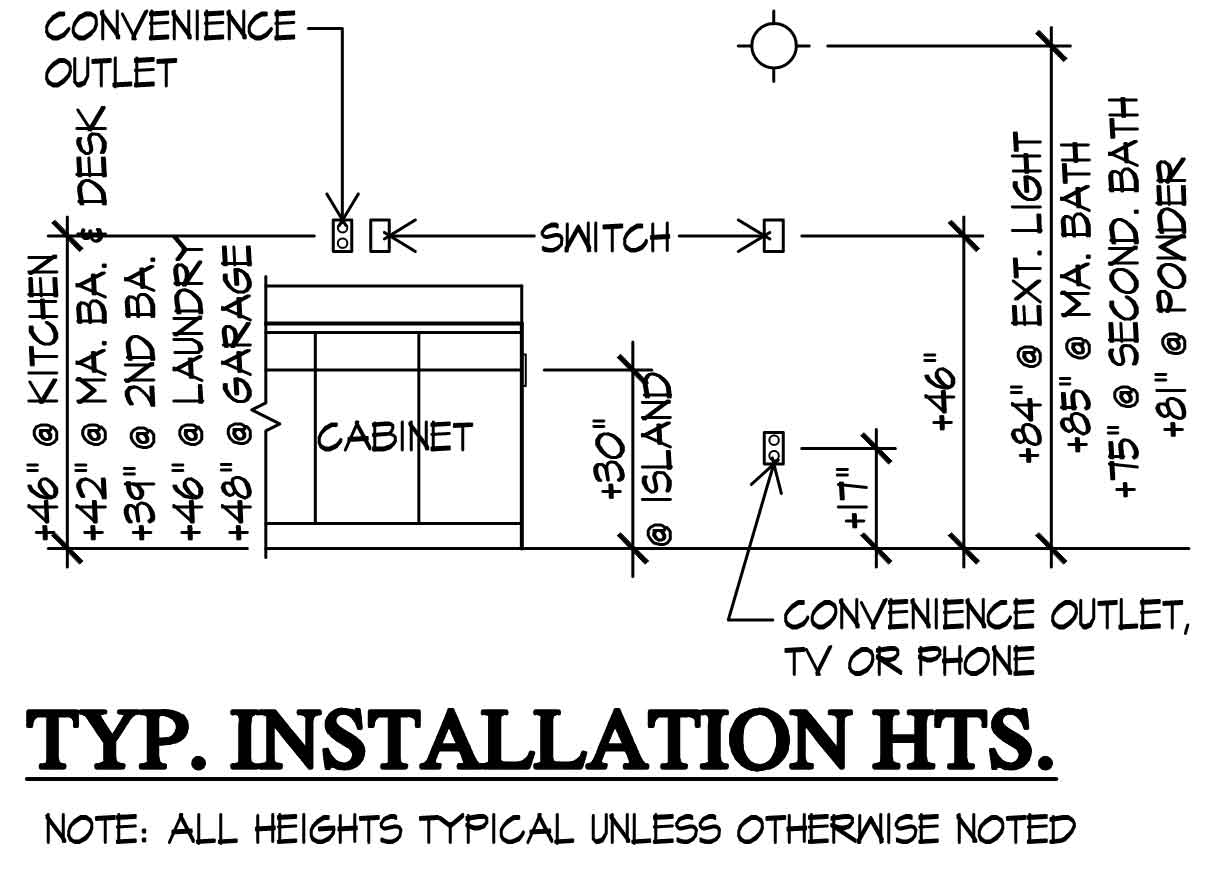

KITCHENS: Give the kitchen more space, and create a variety of work surfaces. Not every counter needs to be at the same height with cabinets below. Sometimes it’s nice to sit down at a desk height work surface to chop vegetables. Create a variety of storage as well. A full height pantry or a pull out drawer for pots and pans will be much more accessible to an 80 year old person than under-counter shelves.

BATHROOMS: Give extra space for an assistant or mobility device, and if there is more than one bathroom, ditch the bathtub in at least one of them. A fabulous trench drain creates an elegant, level-in shower. Shower heads and shelves at different levels, plus a hand held shower, give lots of options.

Standard ADA locations for grab bar blocking are insufficient. Take it one step further and simply put 1/2” CDX plywood behind all the wallboard to provide flexibility for people to put grab bars anywhere they are needed later…without drilling test holes to find the blocking.

CONVERTIBILITY: When designing a new home, consider putting a full bathroom on the ground floor. Ideally, there would also be a bedroom, or a room that can easily convert. In my practice we do a lot of Universal Design work. Many clients have gradually given up using their second floor of their homes for lack of access, and have a bed in the dining room and only a half bath downstairs for sponge baths. What if the original building designers had thought ahead a little more so that people could just age gracefully in their homes?

This brings up another reason for including thoughtful access on Day One: Responsible use of materials and money. In situations like with the clients above, we install stair lifts or elevators, enlarge bathrooms, knock out walls, etc. Some of these homes were remodeled just a few years earlier, and all those materials are entering the waste stream. Not good.

These strategies are just a beginning. Talk to your client about the reality of growing old, and help them future-proof their lives by understanding that an accessible home can work better for them, for visitors, and for older parents who might move in. It’s a home that flows better, that is more usable, and more comfortable. Forever.

Erick Mikiten, AIA

Comments from Kerwin – The concept of “ Aging in Place” offers the owner a level of comfort. I know people building a home today that have included a place for an elevator in their multi-story design. A simple code tool would be apply the requirements in Chapter 11A of the CBC and see how many of the items you can include without losing too much space or adding to the cost.

There is a term using in the Federal Fair Housing Act (FFHA) and in the California Building Code (CBC), “Adaptable”. You will find it in Chapter 2 of the CBC – “ADAPTABLE. Capable of being readily modified and made accessible.”This term has never been truly defined by either the Feds or the State. Is the changing out of hardware, knob to lever, an adaptable feature? What about removable base cabinets? These have all been debated.

Although wheelchair users are still a small number, becoming disabled includes a lot of different disabilities from hearing and sight impaired to having arthritis and not having full capabilities of your hands or feet. A little additional planning in your design could allow someone to live longer and have a happier life in their home.

Kerwin Lee, AIA