Demystifying California Code Changes

Erick Mikiten, AIA, LEED-AP

Before becoming a Building Standards Commissioner in 2012, the timing of the various blue and yellow code book pages that were mailed to our office often felt random. There’s actually a clear and intentional process at work behind the scenes, but since it’s made up of two overlapping cycles, it can feel random when we get those inserts.

Despite the isolation and time-stopping aspects of working at home during the Pandemic, the California Building Standards Commission and an array of State agencies have been feverishly having (virtual) public hearings, editing, and adding to the California Building Code (CBC).

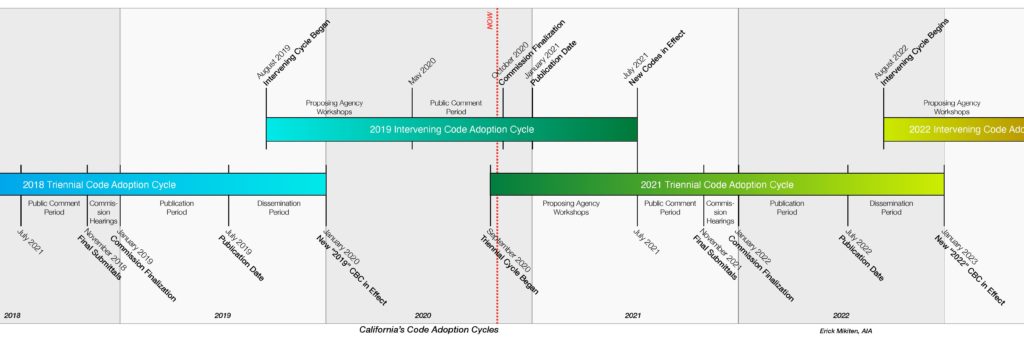

More new changes being published in January 2021, so this is a good time for an overview of the code change process. I’ve distilled the process down to this (long) chart, which is explained below.

But first, let’s take a moment to address those blue and yellow pages…

The Sheets

The yellow sheets are simple: They are Errata. Sometimes they fix a tyypo, sometimes a reference to a code section needs to be updated or corrected. An errata sheet can’t make any substantive change to the code.

The blue sheets are Supplements, and get published when there is a change that has what we call “regulatory effect”. More on what prompts those is below.

Triennial Cycles

Architects entering the profession quickly learn that there is a new full CBC published every three years. Obviously, the vast majority of the CBC is carried over year-to-year, but enough new language trickles down from other sources that everything needs a fresh re-collating and reprinting that often. These sources are the “Model Codes” such as the International Building

Code, National Electrical Code, Uniform Plumbing Code, etc. Model Codes are revised every three years (sometimes substantially), which sets the schedule for State publication of their codes, called the Triennial Code Adoption Cycle.

In addition to reflecting new model code language and requirements, there are also a number of State Agencies assigned to maintain different parts of the code, and they may have new elements to propose. At the beginning of every chapter of the CBC there is a Matrix Adoption Table that tells you what state agencies have adopted and enforces each part of the code.

For example, if you look at Chapter 6 (Roof Assemblies) of the California Residential Code, you’ll see that both the State Fire Marshall (SFM) and the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) have adopted that chapter. This lets the code user know what agencies enforce the adopted portion of the code. The enforcing agency also would provide any interpretation of what’s written. If you’re having an interpretation disagreement with your local building official, you could contact the enforcing agency for more background, or for a written interpretation.

The Triennial Cycle language is printed on new white pages and given a new name based on the year it’s published. You get an opportunity to pay a small fortune for the new books and find space on your bookshelves. And now we can pay for an online, searchable and bookmark able version as well. I use our subscription 2/3 of the time, but it can’t completely replace the usability and immediacy of a dog-eared, sticky-noted, underlined hard copy.

Intervening Cycles

Here’s what confused me when I started working in our Golden State: The Intervening Code Adoption Cycles occur roughly midway between Triennial Cycles, and are the main source of those blue Supplement pages we painstakingly add into our hard copies. Intervening Cycles often focus more on California-specific code changes, rather than the trickle-down from Model Codes.

This year was a perfect example of that. The International Code Council (which creates the International Building Code) has been working on standards for Mass Timber construction that would allow mid-rise and high-rise wood buildings. It’s very exciting stuff – do a Google search on it and you’ll see compelling images of tall wood buildings with exposed beams and columns, and read about the environmental benefits of creating buildings out of a renewable resource that that actually sequesters carbon, rather than concrete and steel that have many more negative environmental impacts at the beginning and end of their useful lives. You’ll see why California got excited about it and decided to adopt it before the new language was officially complete and published.

Entering at stage left: The Intervening Cycle. It gave California a process by which we could get Mass Timber construction before it trickles down through the standard channels. So while the Triennial Cycle wouldn’t have let us start creating Mass Timber buildings until 2023, the Intervening Cycle will give us Mass Timber in July of 2021 (see chart).

Although the Intervening Cycle is the source of most of the blue Supplement pages, the other source is…

Emergencies!

A code emergency may sound like something from an episode of Grey’s Anatomy, but it’s not. If the Governor makes an Executive Order, or if a new law is passed by the State Legislature that require immediate new accessibility standards, recycled water usage requirements, or provision of electrical vehicle charging stations, to mention just a few, an Emergency Adoption process begins. It’s fast, triggering an immediate public hearing for the Commission, and takes effect immediately. This is in stark contrast to Triennial and Intervening Cycles, which have a required180-day period between adoption and the new code becoming effective, allowing building departments to train staff and code users to learn the new requirements and plan their

current projects for permit application.

In order to have some checks-and-balances, Emergency Adoptions require the proposing State agencies to undergo the same public workshops, outreach, and comment period as a regular proposal, but AFTER the adoption by the Building Standards Commission. The Emergency Adoption expires after 180 days if the proposing agency doesn’t go through that process and a “final adoption” that makes it permanent.

Summary

So with new code books every three years, a slew of blue Supplements about 18 months after that, randomly-arriving blue Supplements for Emergency Adoptions, and the odd yellow Errata arriving whenever a code user finds an “oops”…it’s no wonder that the code process seems random.

But just like the sun’s position shifting slowly with the seasons, there is a broader code-change pattern going on in the background as well. Hopefully this description and chart will help making a little more sense of that for you in the future, and help you and your projects anticipate upcoming code changes as well.

Take a look at www.dgs.ca.gov/BSC/Rulemaking for more detail about the code process, to see the details of new code changes in the pipeline, to see when and how YOU can weigh in on future code changes. After 8 years on the Building Standards Commission I’ve seen that there are a relatively few voices providing feedback, so there’s a real opportunity to be heard and have an impact on California’s future codes.

Comments by Kerwin Lee, AIA, CASp:

The basic schedule for code changes is pretty straight forward. Although the State agencies try and follow the timeline for the process, most of the time is eaten up by the agencies, which reduces the time for the public to respond. This is what happened during the latest Intervening Cycle. When code changes are made public by an agency, they first go to a Code Advisory Committee. These committees are made up of professionals representing building and fire officials, construction industry, people with disabilities, architects, and engineers. The committee reviews the proposed changes and provides a recommendation for approval, amendments, or disapproval. Sometimes a proposed change is sent back for further study. In this cycle, the committee I was on, Building Fire and Other, was given less than two weeks to review over a thousand page document of changes. Far too short a time for the committee and public before the formal hearings.

The second problem is the Code Advisory Committee is just that, advisory and has no real clout. The State agency can completely ignore any recommendations from the committees and bring forth a code change with no alterations. This is what I think is a failure in the system. A State agency has all the power to first make proposed changes and then have a code put before the Building Standards Commission without following Advisory recommendation or even public comments. This is what you will see in the coming Tall Wood Building sections when they are published. Instead of adopting what is directly in the 2021 IBC, the State made some changes, reducing the height requirements. In my opinion, these were not justified changes. You can refer to my previous ARCHnews article on Tall Wood Buildings, April-May 2020.

State Agencies are supposed to write code changes based on regulations created in the State by the Legislators or Governor or propose changes that clarify the intent for State needs. They do not have the authority to just write code on their own without justification. Lately the State Agencies have been taking advantage of the system’s lack of control and proposing changes that are beyond their scope and without justification. The biggest issue are code

changes from the Model Codes, which are our national standards. These have been made without justification on why we need it in the State where no other State has these requirements.

We want the codes to change to reflect better understandings of the construction industry, to help clarify what is in the code and changes based on regulations. I am in the belief that if it ain’t broken, don’t change it. The codes are not absolute in guaranteeing safety. Codes reflect how we live. Risk is never eliminated and safety is not absolute, we live with something in between.