Disabled Access – Changes to ANSI A117 and More by Kerwin Lee, AIA

Building regulations reflect society’s needs and are a minimum standard of what we want in our buildings. If you don’t think that you have a stake in this, you are wrong. The loudest voices are the ones that are mostly heard. These are voices that attend code development hearings and work in the political arenas to bring forth their agenda. Most of the time, the agenda serves society as a whole, but other times it is sometimes self-serving and driven by special interests. Special interests would include special political groups or organizations. The codes are for the most part a consensus document, but only by those who are interested.

The building regulations need to change and evolve to reflect changes in technology and understanding of ways to promote the intent of the code. Recent code changes reflect more sociological movements, Green Buildings, environmental and energy conservation.

The first edition of ANSI A117.1 was created in 1961, predating both the Federal Fair Housing Act (FFHA or FHA) and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). In 1959 the President’s Committee on Employment of the Physically Handicapped convened dozens of organizations such as the American Foundation for the Blind, the US Conference of Mayors, architects, and others to create the first standards for architectural accessibility. This was later taken on by the American Standards Association (ASA), later becoming American National Standards Institute or ANSI. The original ANSI A117.1 document was just six pages long. It was one of the first recognized sets of Accessibility Guidelines to be referenced. As a referenced Guideline, it was not a building code.

The A117.1 has become the primary reference Standard for disabled accessibility elements. It has been used as the basis for compliance with both the FHA and ADA Standards. It is now the referenced standard for the International Building Code (IBC) for compliance with Chapter 11 – Accessibility, which is not used by the State of California.

The A117.1 document is under the umbrella of the International Code Council (ICC) and is on a five-year cycle for changes. The most recent edition was the 2017, now titled as the ICC A117.1. They are in the final stages of reviewing and approving the next edition. For more about the ICC process and the see the proposed changes go to: https://www.iccsafe.org/icc-asc-a117-1/ website for the latest.

Changes to the code are important to keep the code current and improve its application in meeting the intent. Among the 100’s of proposed changes, here are some of the proposed changes including the following:

- Bottle filling stations reach ranges

- Electric vehicle charging stations

- Classroom acoustics to reduce ambient noise

- Elevator controls

- And Adult Changing Tables, which is already in the California Building Code (CBC).

Most of the proposed changes are minor adjustments in what is already in the code to help clarify the intent and/or make dimensional adjustments. Although these proposed changes will not directly affect what we do in California, if you do any work outside of the State where the IBC is used with reference to the ICC A-117, you will be required to comply.

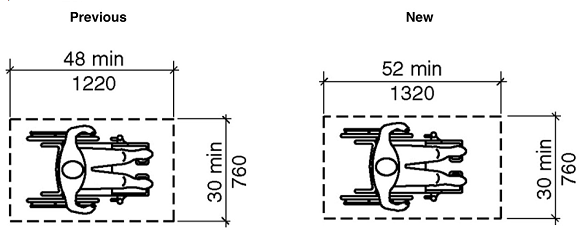

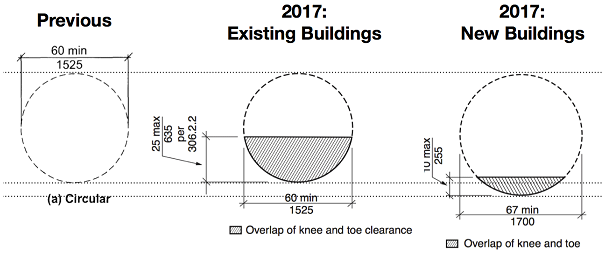

The requirement for Adult Changing Table originated in California, which came from an Assembly Bill, AB 662 and found in Section 11B-813 of the CBC. This law made it a requirement to have Adult Changing tables incorporated into certain types of facilities. This element has made it to the national level and is being proposed for the A117.1 for codification. On the flip side, A117.1 in its last revision (2017 edition) changed the clear floor space for a wheelchair from 48 inches to 52 inches and the turning radius from 60 inches to 67 inches. These values are not found in either of the Standards for the FHA or the ADA. California has not adopted these requirements.

The current A117.1 standards make many adjustments to maneuvering spaces, reach ranges, and other clearances that are more realistic today. Some seem broad and others dramatic, but it’s notable that in many areas, Australian and UK codes have space requirements that are larger than in the new A117.

Changes to the A117.1 or even within State Code that are not found in either of the Federal standards, may be considered as raising the level of access. Because it is not codified in the ADA Standards, it is not required for compliance with the American with Disabilities Act (ADA), at least at this time. Changes to the ADA are slow, and with Washington in a quagmire, don’t expect any of the A117 requirements to show up in the ADA soon. That raises the question for compliance with the Federal Laws. Does complying with any of the National, State or Local codes provide compliance with the ADA? This is called a “Safe Harbor”. Does compliance with a National standard,like the A117.1, provide the assumption of providing an equivalent level of access, in the mind of the courts?

The term Safe Harbor has been codified once by Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The 2009 edition of the A117.1 was labeled a Safe Harbor for compliance with the FHA. The 2017 edition has not received this label. The Department of Justice (DOJ) has not certified any codes recently as a Safe Harbor for the ADA. DOJ and HUD do not appear to be interested in certifying codes. It is a never ending process, because everytime a new edition is created, it needs to be re-evaluated for compliance.

Remember that California does not adopt or use ICC A117.1 as a standard for their building code; we have our own Chapter 11A and 11B, which is unique and different from the IBC. California is just beginning their code development cycle for the next edition of the codes. It will be interesting to see what of the new standards makes its way into the CBC and in what form. As this process continues on different tracks, alignment becomes harder and harder. Although the State Accessibility requirements found in Chapters 11A and 11B will differ from the A117.1 and even the Federal Standards for the ADA and FHA, the bottom line for designers is compliance with the applicable codes for the project.

Kerwin Lee, AIA/Retired

Responses